Hey there, Business Hackers!

Welcome to another edition of Business Hacks & Theories! If you enjoyed our last issue, “Why I Celebrate Failures: Robert H. Goddard’s Journey,” get ready because this time we’re diving into another fascinating aspect of behavioral economics:

the “endowment effect.”

Yes, that little bias that makes us overvalue what we already own. Ready to discover how this influences the business world?

Let’s get started!

What is the Endowment Effect?

Imagine you receive a special pen at a corporate event. It’s not just any pen; it’s engraved with your name, a gift specifically for you. Now, if someone offered to trade it for an equally expensive but non-engraved pen, you’d likely refuse. This pen isn’t just a writing tool; it’s become a part of you, a symbol of the recognition you received. This is the endowment effect in action: a cognitive bias that leads us to overvalue what we already own.

The endowment effect was brought to light in the 1980s by Richard Thaler, but its psychological roots run deep. The theory behind it is that we assign greater value to objects we own compared to those we don’t, primarily due to emotional attachment and loss aversion. Losing an owned object is perceived as more painful than gaining the same object if we didn’t own it.

Before the advent of behavioral economics, traditional economics viewed the consumer as a rational optimizer. According to this view, consumers made purchasing decisions based on a rational analysis of costs and benefits, aiming to maximize their total utility. This theory assumed that people were perfectly informed, logically consistent, and immune to emotional or cognitive influences.

Issues with Economic Predictions: This traditional view led to often inaccurate economic predictions. For instance, it was expected that consumers would respond promptly and rationally to price changes, but real reactions were often slow and non-linear. Economists were puzzled by why consumers didn’t switch suppliers or products even when better offers were available.

Examples of Predictive Failures:

- Real Estate Prices: Traditional theories couldn’t explain why homeowners were reluctant to sell during market downturns, preferring to keep their properties despite depreciation.

- Marketing and Launch Prices: New product launches often failed because companies didn’t consider consumers’ attachment to existing products.

- Discount Policies: Temporary discount campaigns were less successful than expected because consumers tended to value their owned products more highly than new offers.

Understanding Real-World Implications

With the groundwork laid, it’s crucial to explore how the endowment effect manifests in practical scenarios. Understanding its real-world applications not only highlights the pervasiveness of this cognitive bias but also sheds light on its profound impact on economic behavior and market dynamics. Let’s dive into some concrete examples and studies that reveal the surprising ways the endowment effect shapes our decisions.

Thaler’s Coffee Mug Experiment: Thaler conducted a famous experiment where participants were given a coffee mug and then asked how much they would sell it for. Surprisingly, participants assigned a much higher value to the mug when it was theirs compared to when it wasn’t.

The Sports Tickets Case: Another interesting example involves tickets to sporting events. People who own tickets to a major game often refuse to sell them even at prices much higher than the purchase price. This behavior is a clear sign of the endowment effect: the ticket is not just a piece of paper but represents the future experience and emotion of being part of the event.

Real Estate Market: In the real estate market, homeowners tend to overvalue their homes compared to potential buyers. This can lead to unrealistic asking prices and difficulties in closing transactions. A survey showed that sellers often add an “emotional premium” to their property’s value, complicating negotiations.

Value of Personalized Gifts: Personalized gifts, like photo mugs or engraved jewelry, are especially appreciated by recipients. Even though the market value of the item may be modest, the perceived value is much higher thanks to the endowment effect. This is widely exploited in the marketing of personalized products.

Economic Implications

The endowment effect has profound economic implications that extend beyond the simple perception of the value of objects. It influences various aspects of business and consumer behavior, reshaping how decisions are made in the marketplace. Let’s delve deeper into some of these implications and explore how they manifest in real-world scenarios.

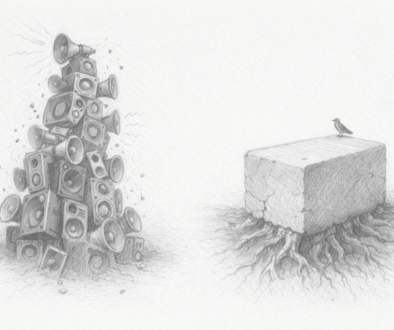

Resistance to Change

In the business world, the endowment effect often manifests as resistance to change. Employees and managers tend to overvalue current processes and practices compared to new proposals, even when the latter could be more efficient or innovative. This phenomenon can significantly slow the adoption of new technologies or methodologies.

For instance, consider Kodak, a company that was once a giant in the photography industry. Despite the clear shift towards digital photography, Kodak clung to its film-based business model for too long, valuing its established processes and infrastructure over new digital opportunities. This resistance to change, fueled by the endowment effect, contributed to the company’s eventual downfall when it failed to adapt to the digital revolution.

Marketing and Sales

Marketing strategies frequently exploit the endowment effect to increase sales. Companies often offer free trials or unconditional refund policies, allowing consumers to try products risk-free. This tactic makes consumers feel as if they already own the item, and once the product is in their hands, it becomes harder to return it due to the endowment effect.

For example, Amazon Prime offers a 30-day free trial, giving users access to its vast range of services, from streaming to free shipping. This trial period allows customers to experience the benefits of the service, making them more likely to subscribe once the trial ends, as they have started to perceive the service as part of their routine.

Investment Valuation

Investors can also be influenced by the endowment effect in their financial decisions. They tend to hold onto stocks they own even when it is clear that selling would be more advantageous. This behavior, known as the “endowment effect bias,” can lead to suboptimal investment portfolios.

Take the example of Warren Buffett’s investment philosophy. While Buffett is known for his long-term investment strategy, he also emphasizes the importance of not getting emotionally attached to stocks. He advocates for rational decision-making and frequently advises against letting the endowment effect influence investment choices. However, many investors still struggle with selling stocks at the right time due to their emotional attachment to their holdings.

Negotiations and Bargaining

In negotiations, the endowment effect can lead to impasses. The parties involved often overvalue what they are offering compared to what they are receiving, complicating the achievement of agreements. This is particularly evident in real estate negotiations and business-to-business transactions.

A practical example can be seen in the merger talks between major corporations. During the failed merger negotiations between Pfizer and AstraZeneca in 2014, AstraZeneca’s management significantly overvalued their company’s worth, influenced by their attachment and the endowment effect. This led to Pfizer’s offers being rejected multiple times, ultimately causing the negotiations to collapse.

The endowment effect is more than just a cognitive bias; it is a window into the complexity of human decision-making and our emotional nature. Recognizing and understanding it allows us to better navigate daily interactions, both personal and professional.

Imagine being able to use this knowledge to improve your marketing strategies, optimize your negotiations, or simply better understand consumer behavior. The endowment effect teaches us that value is not just a matter of price or utility but also of perception and emotional attachment.

Reflecting on this bias can help us make more informed decisions and be less influenced by our emotions. It can lead us to be more aware of our attachments and to consider alternatives we might otherwise have dismissed. And in an increasingly complex and interconnected world, this awareness is an invaluable resource.

So, Business Hackers, next time you find yourself evaluating something you own, ask yourself:

“Am I truly considering its real value, or am I influenced by the endowment effect?”

This simple question could make a big difference in your decisions.

Stay savvy, and see you in the next issue!